Page 18 - IB June 2020

P. 18

PNG PNG

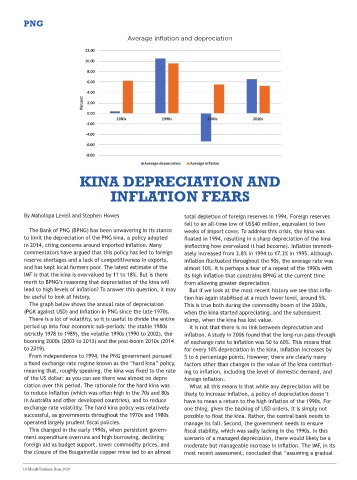

Average inflation and depreciation

KINA DEPRECIATION AND

INFLATION FEARS

By Maholopa Leveil and Stephen Howes total depletion of foreign reserves in 1994. Foreign reserves

fell to an all-time low of US$40 million, equivalent to two

The Bank of PNG (BPNG) has been unwavering in its stance weeks of import cover. To address this crisis, the kina was

to limit the depreciation of the PNG kina, a policy adopted floated in 1994, resulting in a sharp depreciation of the kina

in 2014, citing concerns around imported inflation. Many (reflecting how overvalued it had become). Inflation immedi-

commentators have argued that this policy has led to foreign ately increased from 2.8% in 1994 to 17.3% in 1995. Although

reserve shortages and a lack of competitiveness in exports, inflation fluctuated throughout the 90s, the average rate was

and has kept local farmers poor. The latest estimate of the almost 10%. It is perhaps a fear of a repeat of the 1990s with

IMF is that the kina is overvalued by 11 to 18%. But is there its high inflation that constrains BPNG at the current time

merit to BPNG’s reasoning that depreciation of the kina will from allowing greater depreciation.

lead to high levels of inflation? To answer this question, it may But if we look at the most recent history we see that infla-

be useful to look at history. tion has again stabilised at a much lower level, around 5%.

The graph below shows the annual rate of depreciation This is true both during the commodity boom of the 2000s,

(PGK against USD) and inflation in PNG since the late 1970s. when the kina started appreciating, and the subsequent

There is a lot of volatility, so it is useful to divide the entire slump, when the kina has lost value.

period up into four economic sub-periods: the stable 1980s It is not that there is no link between depreciation and

(strictly 1978 to 1989), the volatile 1990s (1990 to 2002), the inflation. A study in 2006 found that the long-run pass-through

booming 2000s (2003 to 2013) and the post-boom 2010s (2014 of exchange rate to inflation was 50 to 60%. This means that

to 2019). for every 10% depreciation in the kina, inflation increases by

From independence to 1994, the PNG government pursued 5 to 6 percentage points. However, there are clearly many

a fixed exchange rate regime known as the “hard kina” policy, factors other than changes in the value of the kina contribut-

meaning that, roughly speaking, the kina was fixed to the rate ing to inflation, including the level of domestic demand, and

of the US dollar: as you can see there was almost no depre- foreign inflation.

ciation over this period. The rationale for the hard kina was What all this means is that while any depreciation will be

to reduce inflation (which was often high in the 70s and 80s likely to increase inflation, a policy of depreciation doesn’t

in Australia and other developed countries), and to reduce have to mean a return to the high inflation of the 1990s. For

exchange rate volatility. The hard kina policy was relatively one thing, given the backlog of USD orders, it is simply not

successful, as governments throughout the 1970s and 1980s possible to float the kina. Rather, the central bank needs to

operated largely prudent fiscal policies. manage its fall. Second, the government needs to ensure

This changed in the early 1990s, when persistent govern- fiscal stability, which was sadly lacking in the 1990s. In this

ment expenditure overruns and high borrowing, declining scenario of a managed depreciation, there would likely be a

foreign aid as budget support, lower commodity prices, and moderate but manageable increase in inflation. The IMF, in its

the closure of the Bougainville copper mine led to an almost most recent assessment, concluded that “assuming a gradual

18 Islands Business, June 2020